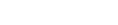

Earlier this week, Revolut closed its Series D funding round where it successfully raised $500 million in a round led by TCV. This puts Revolut at a valuation of $5.5 billion, placing it in the top 10 most highly valued fintech unicorns so far. Discounting Ant Financial’s awe-inspiring valuation of over $150 billion, the unicorns’ list is currently led by Stripe, valued at an impressive $35.25 billion, over double the value of current runner-up, One97 Communications. Of the 60 fintech start-up unicorns recorded so far, 58 of them have cracked the $1 billion ceiling in just the last five years.

Click here to download a list of all the fintech unicorns today.

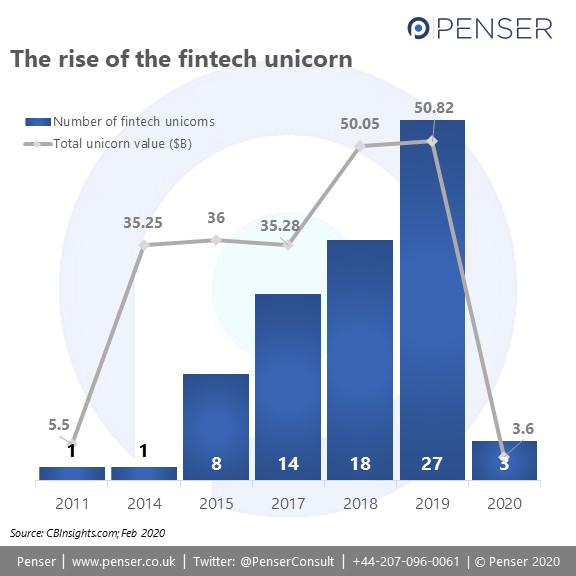

Aside from these unicorns, the fintech industry overall has seen considerable investment. Overall, global investment in fintech was at $135.7 billion across 2,693 deals (largely driven by FIS’s acquisition of Worldpay for $42.5 billion and First Data’s acquisition by Fiserv for $22 billion). VC-backed fintech deals and financing hit close to $35 billion in 2019 across almost 2,000 deals. This was still lower than the peak hit in 2018, but still significant.

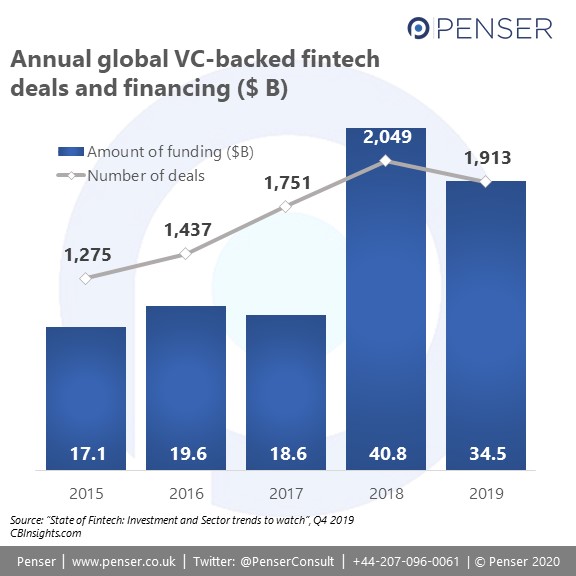

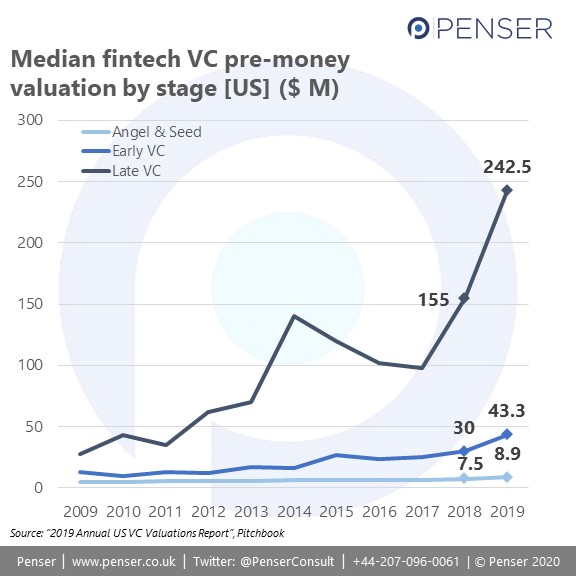

Similarly, 2019 was a record year for “mega-funding” rounds (or rounds with more than $100 million invested), with record values being hit in every market besides Europe. Almost half of 2019 funding was concentrated in these mega-rounds. The median pre-money valuations by VC of fintech start-ups has also significantly increased in the last two years, indicating a willingness to sink large amounts of funding in these companies.

As a result of these more-frequent mega-rounds, fintech start-ups are maturing beyond early-stages and choosing to raise private funding over going public. These mega-rounds have emerged as an acceptable financing option to going public across industries – a sentiment that has been bolstered by recently IPOs that have grossly underperformed, such as Uber and Lyft. Even GreenSky, a point-of sale financing and payment solutions provider, has dropped from its peak share price of $26.66 (a market cap of around $5 billion) on June 1, 2018, to $7.66 (a market cap of close to $1.4 billion) on February 27, 2020, indicating that even the fintech sector is not immune to such failures.

Presumably, these private investors are investing heavily in the sector because they recognize that fintech is expanding rapidly, and therefore, the sector is more likely to let them realize high returns on their investments. But many of these companies are yet to break even, let alone record a net profit.

This begs the question – how do investors evaluate these companies, and justify the large price tag they associate with them?

Company Valuation – The Traditional Approach(es)

Before we delve into how one can derive a value for our fintech start-up, let’s take a quick run-through the more traditional methods of valuing companies. Please note: we’re listing the standard approaches here – not all of these may apply to a start-up. This list is also not an exhaustive list of every approach, but it does cover some of the more common financial models used for determining a company’s value.

1. The Discounted Cash Flow (DCF) method:

The DCF model forecasts your cash flows for up to 5 years with an estimated ‘terminal’ value at Year 5. This value should reflect your assessment of the nature of the business at that point. These cash flows and the terminal value are then discounted at the average cost of capital to arrive at a present enterprise/equity value.

2. The revenue / profit / EBITDA / book value multiple method:

These valuations are built on the back of key operational metrics that could give a reasonable estimation of the company’s success. Through reasonable estimation, a multiple can be derived which can be used to attain a value for the company. Sometimes, these multiples can also be used in the DCF method above to determine the terminal value.

3. Replacement costs:

If the business has hard-to-replace assets that may take time and money to build, then the value of replacing those assets can be used as a benchmark to build a valuation model of the company.

4. Price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio:

Using the P/E ratio, future earnings per share (EPS) can be determined and used for valuing the business.

5. Strategic/competitive value:

This is a little more qualitative in nature. In certain cases, the company may be a competitor, or pose a significant threat to an existing business. As a result, the value of that potential impact may be used to determine the value of the company.

6. Comparable public companies:

A model is built based on comparable public companies and the multiples derived from their operating metrics. These are then applied to your business. The veracity of this model depends on how similar the comparison company is, and any discounts you might need to factor in to account for the higher risk involved.

7. Comparable precedent transactions:

This is along the lines of the above, with a crucial difference; in this case, you use other investments or acquisitions in similar companies as your benchmark, and derive a suitable transaction multiple to apply to your business. This model will also need to factor in the market conditions at the time, deal synergies, and any premiums paid above equity value, among others.

Now, when you consider the above models in the context of fintech start-ups, some of these look difficult to apply. This is especially on those models that depend on revenues, profits and cash flows, which may be negative for these start-ups. If you factor in the agile nature of their business model and the ability to quickly pivot as needed, along with the negligible physical assets involved, and the waters get murkier. Even using comparable precedent transactions as your benchmark may not provide an accurate picture, as it depends on previous valuations having been accurate. Some may even argue that comparing to precedent transactions is what led to the dot-com bubble in the ‘90s.

Of course, this is just a broad overview of the way valuation models can be built. There will be nuances that need to be taken into account depending on what kind of finance company we’re dealing, especially when it comes to traditional institutions. For instance –

- Banks traditionally run on a business model that depends on the spread between deposits and loan rates. As a result, default rates and management of the capital structure pay a crucial part in understanding the value of the bank. Therefore, relevant metrics would be net interest margins and return on assets, which consider the bank’s efficiency and capital deployment, and, of course, P/E and EPS multiples, which account for the capital structure and expected growth, and the resultant shareholder returns.

- Asset management companies, like those dealing with mutual funds, are typically valued as a percentage of their assets under management (AUM). This is because their AUM indicates the company’s ability to generate cash flow based on the total funds available. You can even correlate income growth with the size of the fund by comparing AUMs with the firm’s market capitalization. Other factors that could make an impact include the size of the investor base, the ratio of growing versus stable base of investors, and the type of fee structure followed (public and regulated versus private and less- or non-regulated).

- Wealth management firms, while similar to mutual funds, differ in a few significant ways. While mutual funds tend to be more regulated and process-oriented, wealth management firms tend to depend a lot on customized solutions for clients based on their appetite for risk, and the personal relationship between the client and the manager. As a result, correlating their value with its AUM is not enough; additional variables that take these specific factors into account are needed to provide a more comprehensive picture.

- Aside from common measures such as return on equity, there are some other factors that would be more relevant to insurance companies, such as premium growth. When premium growth in the company is compared to the average in the market, it gives an indication of whether the company is gaining market share, or if the market is becoming more saturated. Another key factor is the consistency of returns or income over longer periods. This helps provide a more accurate picture of the business’s health than a model based on payout ratios, which tend to be more volatile. Lastly, it’s also important to take into account other comprehensive income (OCI). OCI is basically income from investments, which, along with premium income, constitutes the key source of income for an insurance company.

With that, we come to the end of this part of our series. In our next post in the series, we look at how start-ups are usually valued, and what are the methods VCs and other investors use when trying to determine the right pre-money valuation.

Penser provides expert consulting services in the payments and fintech sectors, and therefore, we pay close attention to key changes in regulations and innovations in the industry. We act as advisors to a number of financial clients on their digital transformation journeys, as well as support them with due diligence and strategic planning services. Click here to contact us for more information.